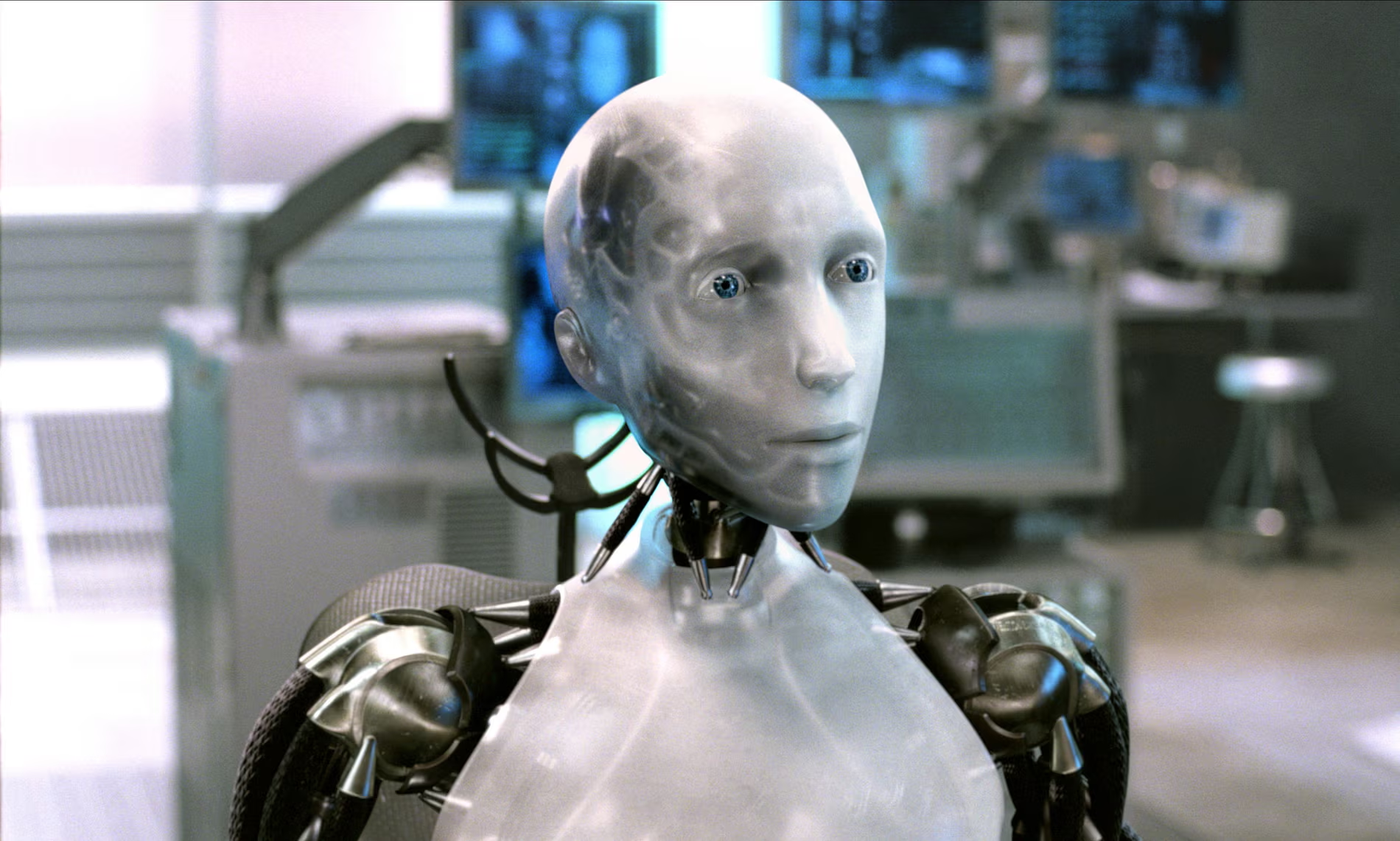

Hiroshi Ishiguro, a professor at Osaka University’s Intelligent Robotics Laboratory, with Erica, his latest humanoid robot. Photograph: Justin McCurry for the Guardian

Although the day when every household has its own robot is some way off, the Japanese are demonstrating a formidable acceptance of humanoids

Justin McCurry in OsakaThu 31 Dec 2015 08.48 GMTLast modified on Wed 29 Nov 2017 05.03 GMT546

Erica enjoys the theatre and animated films, would like to visit south-east Asia, and believes her ideal partner is a man with whom she can chat easily.

She is less forthcoming, however, when asked her age. “That’s a slightly rude question … I’d rather not say,” comes the answer. As her embarrassed questioner shifts sideways and struggles to put the conversation on a friendlier footing, Erica turns her head, her eyes following his every move.

It is all rather disconcerting, but if Japan’s new generation of intelligent robots are ever going to rival humans as conversation partners, perhaps that is as it should be.

Erica, who, it turns out, is 23, is the most advanced humanoid to have come out of a collaborative effort between Osaka and Kyoto universities, and the Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International (ATR).

At its heart is the group’s leader, Hiroshi Ishiguro, a professor at Osaka University’s Intelligent Robotics Laboratory, perhaps best known for creating Geminoid HI-1, an android in his likeness, right down to his trademark black leather jacket and a Beatles mop-top made with his own hair.

Erica, however, looks and sounds far more realistic than Ishiguro’s silicone doppelganger, or his previous human-like robot, Geminoid F. Though she is unable to walk independently, she possesses improved speech and an ability to understand and respond to questions, her every utterance accompanied by uncannily humanlike changes in her facial expression.

Erica, Ishiguro insists, is the “most beautiful and intelligent” android in the world. “The principle of beauty is captured in the average face, so I used images of 30 beautiful women, mixed up their features and used the average for each to design the nose, eyes, and so on,” he says, pacing up and down his office at ATR’s robotics laboratory. “That means she should appeal to everyone.”

She is a more advanced version of Geminoid F, another Ishiguro creation which this year appeared in Sayonara, director Koji Fukada’s cinematic adaptation of a stage production of the same name.

The movie, set in rural Japan in the aftermath of a nuclear disaster, made Geminoid F the world’s first humanoid film actor, co-starring opposite Bryerly Long. While robots in films are almost as old as cinema itself, Erica did not rely on human actors – think C-3PO – or the motion-capture technology behind, for example, Sonny from I, Robot.

Although the day when every household has its own Erica is some way off, the Japanese have demonstrated a formidable acceptance of robots in their everyday lives over the past year.

From April, two branches of Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group started employing androids to deal with customer enquiries. Pepper, a humanoid home robot, went on sale to individual consumers in June, with each shipment selling out in under a minute.

This year also saw the return to Earth of Kirobo, a companion robot, from a stay on the International Space Station, during which it became the first robot to hold a conversation with a human in space.

And this summer, a hotel staffed almost entirely by robots – including the receptionists, concierges and cloakroom staff – opened at the Huis Ten Bosch theme park near Nagasaki, albeit with human colleagues on hand to deal with any teething problems.

But increasing daily interaction with robots has also thrown up ethical questions that have yet to be satisfactorily answered. SoftBank, the company behind Pepper, saw fit to include a clause in its user agreement stating that owners must not perform sexual acts or engage in “other indecent behaviour” with the android.

Ishiguro believes warnings of a dystopian future in which robots are exploited – or themselves become the abusers – are premature. “I don’t think there’s an ethical problem,” he says. “First we have to accept that robots are a part of our society and then develop a market for them. If we don’t manage to do that, then there will be no point in having a conversation about ethics.”

Nomura Research Institute offered a glimpse into the future with a recent report in which it predicted that nearly half of all jobs in Japan could be performed by robots by 2035.

“I think Nomura is on to something,” says Ishiguro. “The Japanese population is expected to fall dramatically over the coming decades, yet people will still expect to enjoy the same standard of living.” That, he believes, is where robots can step in.

In Erica, he senses an opportunity to challenge the common perception of robots as irrevocably alien. As a two-week experiment with android shop assistants at an Osaka department store suggested, people may soon come to trust them more than they do human beings.

“Robots are a mirror for better understanding ourselves,” he says. “We see humanlike qualities in robots and start to think about the true nature of the human heart, about desire, consciousness and intention.”

Coming face to face with Erica can be disconcerting. Her ability to express a range of emotions via dozens of pneumatic actuators embedded beneath her silicone skin – left this human momentarily lost for words when invited by Ishiguro to strike up a conversation in her native Japanese.

For the time being, a flawless chat with Erica must revolve around a certain number of subjects, yet experts believe that free-flowing verbal exchanges could be only a few years away.

For that to happen, developers will have to imbue robots with a more humanlike presence – what the Japanese call sonzaikan – rather than settle for the human, but not quite, qualities that can put people on edge in the presence of a moving, talking android.

By Ishiguro’s reckoning, the more they resemble humans – from their physical appearance to their capacity for natural conversation – the easier it will be for us to overcome our phobias, exploited to dramatic effect by countless sci-fi movies.

“They will have to be able to guess a human’s intentions and desires, then refer to an internal system in order to partly or wholly match those intentions and desires in their response,” he says.

He pauses, before asking how that could alter the dynamics of the robot-human relationship. It is a rhetorical question: “It means,” he says, “that one day, humans and robots will be able to love each other.”